I am sitting amid ten large moving boxes for my move to Belgium and in front of me is one box far too heavy to lift, filled with colourfully bound notebooks from my studies. Even if I wanted, I would not be able to find anything specific I was looking for, without flipping through the entirety of the books and then remembering that I had stored the information somewhere completely different. On a bright green post-it somewhere, maybe, or written in the margins of a book. Ctrl/Cmd F doesn’t work on paper, unfortunately, (not yet, at least?) Not an ideal system, then, to hold a PhD worth of information in your brain. So I needed a different system.

A brief history of my note-taking attempts

I have gone through several note-taking systems. In my bachelor’s degree, I took almost all notes by hand in notebooks, and continued to do that into my master’s degree. For my master’s thesis, I used large word documents in which I dumped everything that seemed of interest until I could not find anything anymore. As I continued reading in this research field after graduating, I looked into Notion and really appreciated the possibility of linking my notes to each other. After a while, however, Notion seemed like a tool that wanted to do too much and it became far too complex for me. I copied my entire set of notes back into word documents, only a bit more organised this time. This meant, however, not being able to search for specific ideas. So I looked up alternatives for Notion and found Obsidian, which I have been using ever since.

The thing about note-taking is that the tool itself does not do anything for you if you don’t have a workflow to match it. This thought made me interested in the Zettelkasten method. I am drawing heavily on Söhnke Ahrens‘ (2022) book „How to take smart notes“ here and some videos I have watched on how to implement the idea of the Zettelkasten in Obsidian.

I will explain the basics of the system and how I understand them and implement them in my work flow. I will then detail which kinds of notes I take in obsidian and illustrate this with a couple of screenshots.

At this point, I would like to offer a short disclaimer. As I have described above, my note-taking methods have changed often and they continue to do so. Note-taking is something personal, since it has to match the way your brain retrieves information. As your brain changes through your learning, your needs for note-taking will also change. I will certainly adjust this system again, since I am only starting my PhD next week and don’t really know what awaits me, yet. However, this is a starting point and certainly the most efficient, fun, and useful system I have ever used.

Fundamentals of the Zettelkasten

Writing from the bottom up

One of the core concepts is that you refrain from structuring your notes and putting them into categories. This is especially helpful for my project because I am taking notes on many interdisciplinary subjects. I would have trouble sorting them into specific folders: Does this paper belong with the educational literature or the sustainability transition literature? What if it tackles both topics at the same time? To avoid this categorisation, you just take your notes and make lists later that draw together some of the subjects that emerged.

In obsidian, it is easy to recognise these clusters if you have connected your notes well. Whichever bubble in the graph view is the largest, has the most connections and you recognise quickly the topics that you are most invested in. You can then make overview notes for yourself or an index, to guide your reading of your notes along (more on this under the permanent notes heading later).

This way, you collect ideas without imposing a structure from above but instead build your knowledge basis from the ground up and go with whatever emerges and write from there. Ahrens recognises this as a reversal of how we usually learn to take notes and write, with a strict plan beforehand what we want to find. This is, however, not the way research works, and it stifles creativity (Ahrens, 2022).

Connections are everything

The key element of this system and the most valuable part of this note-taking method are the connections you make between notes. In obsidian you have two ways to do this. You can either refer directly to notes by inserting the title of those notes in square brackets, or you can see through the backlink tab in your programme which note referred to the one you have opened. There are a lot of youtube videos out there detailing how this works, so check them out for a bit more clarity on this.

The advantage of linking notes is that this is similar to how your brain works. Without context, an idea is lost incredibly fast and can even be useless because you don’t know when and in which circumstance to use it. By making connections between thoughts, you ensure that you know in which context to use them, you might even find new contexts to use ideas in. Most importantly, however, it gives you the opportunity to find notes through several different paths (Ahrens, 2022). If I made a note on some obscure concept that I rarely refer to, it will just vanish in the vastness of my literature notes folder. If I make one connection to another note, however, I can now find the obscure concept by clicking on the other note. The more connections you make, the easier notes are to find. This allows note structures to grow organically and things you never use to disappear into the background. In a way, this gives you a prioritisation tool, too.

Writing as thinking

One thing Ahrens is adamant about and that I really appreciate in the book is his description of the writing practice that emerges from this system. Everything you do in this programme is directed towards writing. You think by writing down how you respond to what you have read. Every time a new thought or idea emerges, you make a new note. You go through the notes you already have and look for connections. And when you do, you might notice things you have not noticed before, and you make another note. This allows you to build your thinking around the issues you read about and make original connections that might not have been in the text.

You also get to witness how your thinking evolves over time. You might detect flaws in your logic or contradictions between notes. What do you do when you find those? Yes, you make a note on that, reference both of the notes that contradict each other.

He describes this practice as the basis for writing larger pieces, such as journal articles. If you have done the thought work and developed your argumentation and have all of that in writing already, although still atomised, you have done the bulk of the work of writing. He emphasises that if you think about writing after you have read something or when you are about to write a paper, it is already too late (Ahrens, 2022:60): You have lost thoughts and connections that might have come up in the reading process and now you sit in front of a blank page and don’t know what to do.

This technique, then, is a way to constantly add tiny colourful bricks out of which you can then build a house through figuring out which colour distribution you would like to have and adding a bit of mortar in between. And this metaphor doesn’t even hold completely because you can re-use these bricks for other structures you will be building in the future!

Now that I have outlined the basics of this system, let’s get into how I specifically implement it in obsidian.

Types of notes I am taking in obsidian

The descriptions I give now are quite specific to obsidian but can also be implemented in any other tool that allows for connecting notes (e.g. notion, roam research). If you have not worked with such a system before, I recommend watching a couple of videos, especially those that explain how to use such note-taking systems in academia. I have watched a couple of them before getting started and it helped me immensely.

Fleeting notes

These are, in the Zettelkasten system, the notes that feature quick thoughts you have when you read something. I recently came across the idea of giving more attention to the act of „noticing“ (Klinkenborg, 2012) while reading. We sometimes have physical reactions to something we read, something tickles us, draws us in. We should always follow these intuitions and look into them, follow our interests, because they can open up completely new perspectives.

Fleeting notes are, as their name suggests, only there for the short term. They demand to be written up into proper permanent notes later and connected to other permanent notes. I often have to clear out the folder of fleeting notes because I simply cannot remember what I wanted to say with some of them, if it has been too long.

Literature notes

This is, at the moment, the bulk of the notes I have in obsidian. They look like that in my sidebar, alphabetised and displaying author, year, and a shortened version of the title:

Ahrens and others suggest keeping them brief and using mostly your own words to summarise what is being said (Ahrens, 2022) but I usually have excessive pages of notes for every paper I read. Obsidian has a toggle feature so that you don’t have to see all the content on the first glance but can slowly reveal what you see, a most helpful feature, I must say.

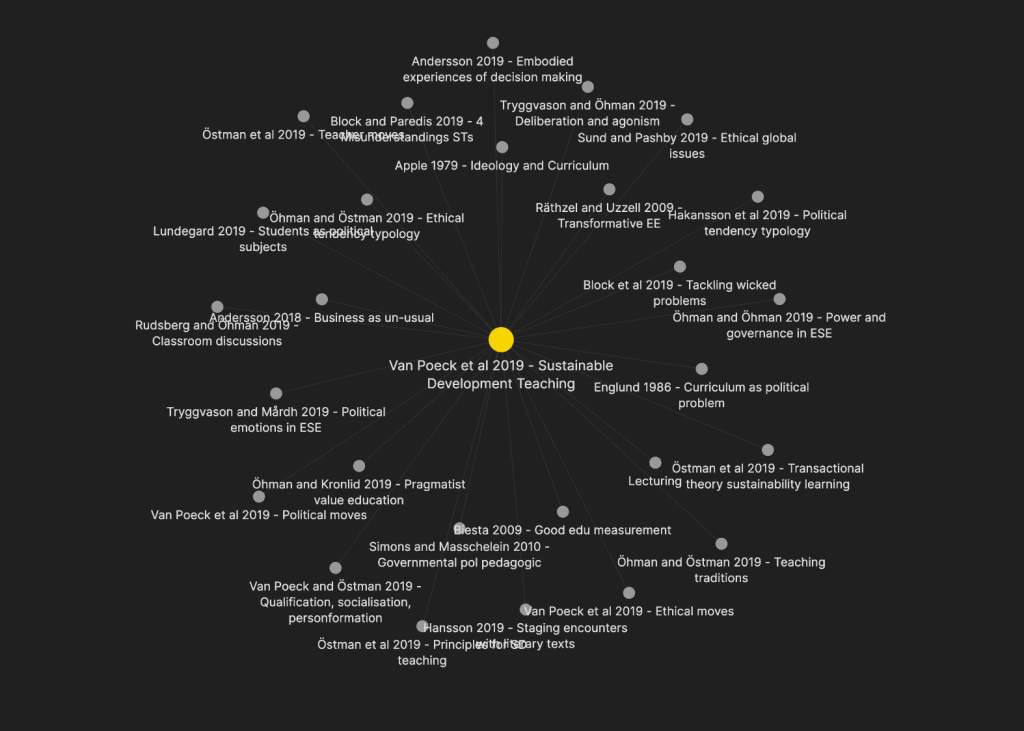

I usually split edited books up in chapters so that referencing them in other notes becomes easier. I will have one page for the edited book and make links to each chapter, complete with author, date, and title. Then, I take separate notes on each chapter. The link tree for the book can then look like this:

Into literature notes, I copy quotes and I write my ideas and thoughts underneath them with a little „>“ in front of them. This way, I can distinguish my thoughts from the thoughts of the person I am quoting. I also use proper reference formatting already so that the writing process will get easier afterwards and I don’t have to search for lost quotes by scrolling through books and papers again.

Permanent notes

These are at the core of the Zettelkasten system. Ahrens describes them as having a conversation with yourself. You alone establish the connections between these notes so the connections in your system will resemble the connections in your brain (Ahrens, 2022).

This is actually the most fun part of the whole technique. Whenever I come across a thought that I want to develop further and want to relate to my research project that I will be doing, I create a new note. I give it a title, set the tag to „permanent note“ and write down a date. This way, I will be able to see how my thinking evolves over time.

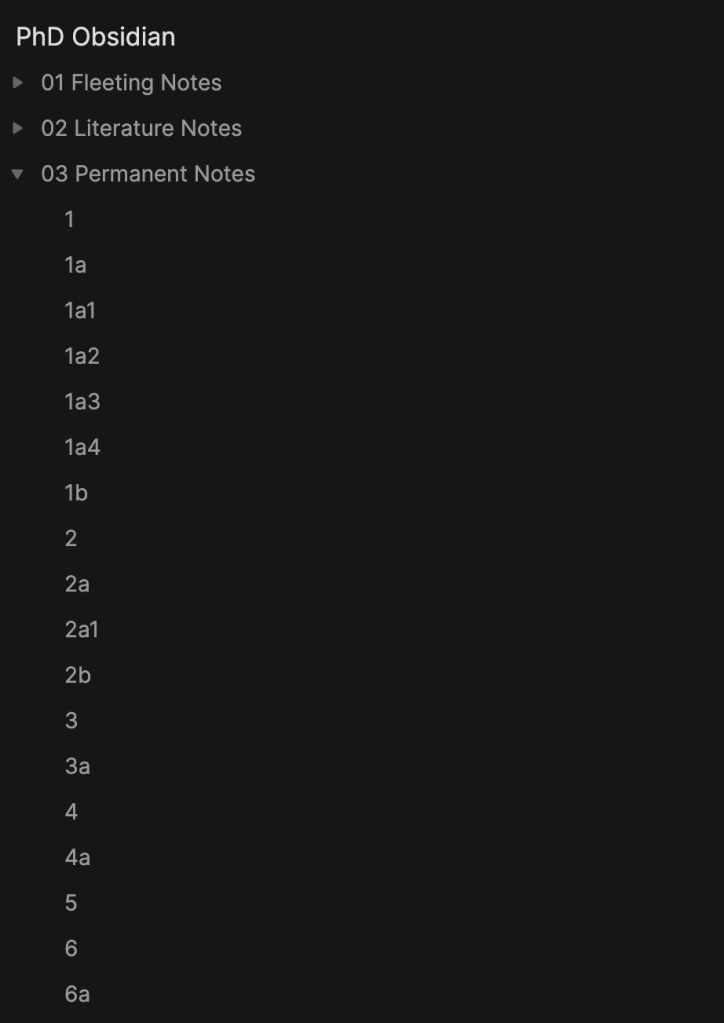

I chose a simple numbering system resembling that of Luhmann, the originator of the Zettelkasten system (as described in Ahrens, 2022). Every time I have a new thought that does not have much to do with the prior thoughts I wrote down, I give the note a number that wasn’t there before. Whenever I want to add on a thought that is already there, I will add either a letter or a number. So if 1a exists already and I want to build on it, I give the new note the designation 1a1. You can see how this works here:

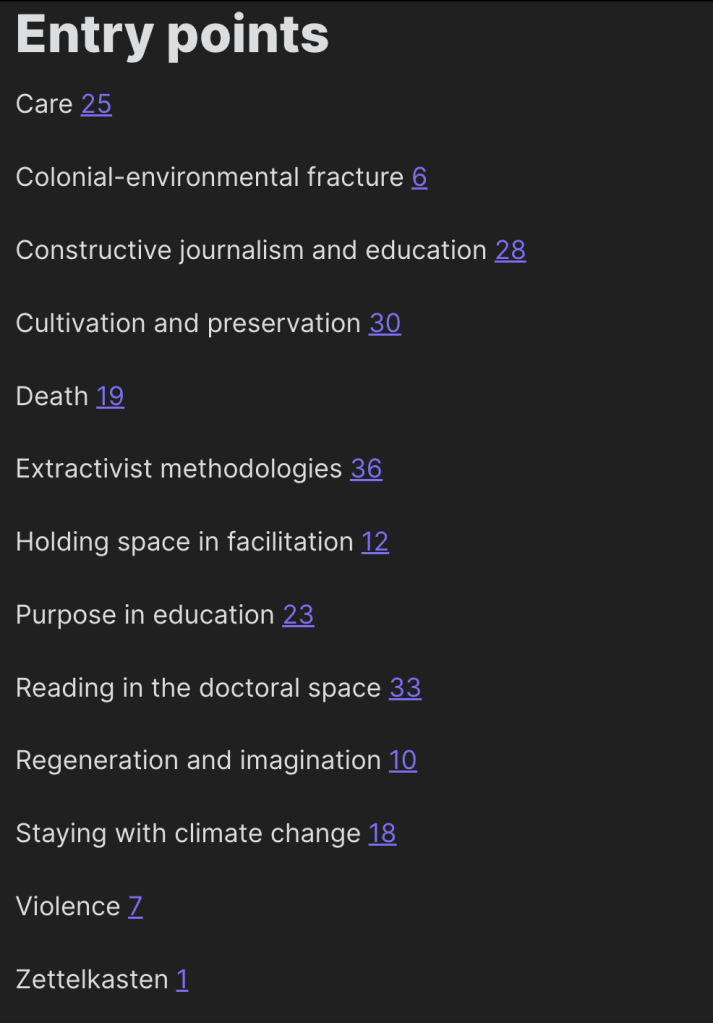

The advantage of this system is that the titles remain short and uncluttered. Also, I need to look through the notes every time and remind myself of what I wrote and what I want to connect a new note to. This way, I remember my lines of thought and have them fresh in my mind. To make this a little bit easier, I am keeping an index with key words that I wrote more about. Through the connections I am creating between the notes, I can click myself through my entire line of argumentation by just starting with one note from the index.

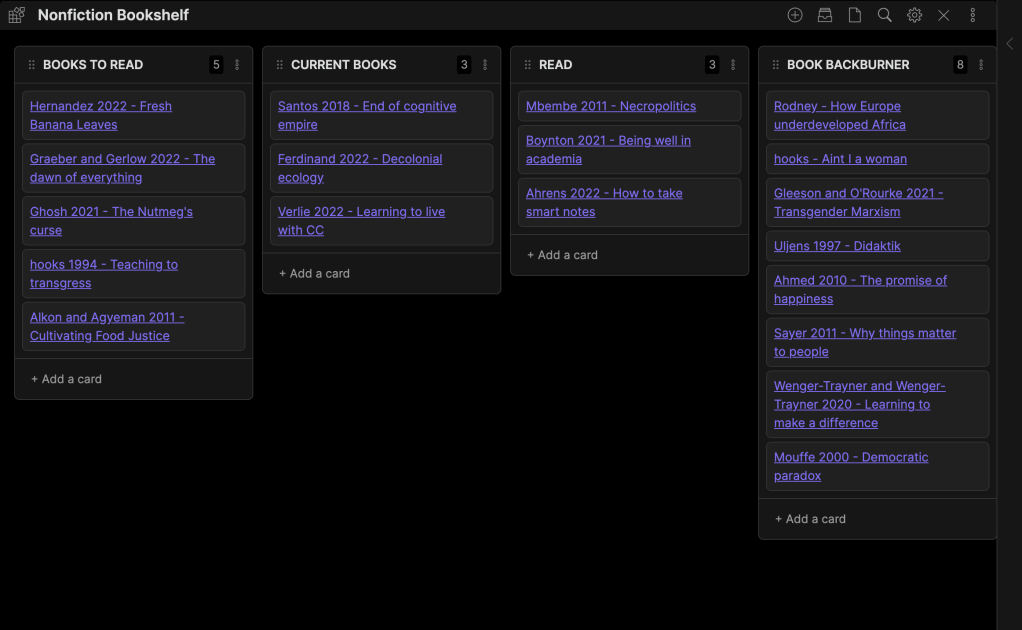

To read lists

I also do some organising of the literature I want to read. I installed the kanban community plugin and made a little bookshelf for myself to keep track of the books I am reading in parallel. I often can’t remember which ones I am actually half way through because I have the habit of picking up new books all the time without finishing any. This board helps me organise this dangerous practice.

I also have an extensive to-read list in which I note down papers and books I want to read, sorted according to different areas of interests I should look into in the PhD.

This is the system I am currently using. It is a lot of fun and it helps me stay active, develop my own thoughts on what I am reading, and keep track of any emerging connections between ideas. My family always teases me because I have the habit of saying „Oh, I read a book about that!“ whenever a random topic comes up. Obsidian allows me to keep track of exactly these thought patterns that are triggered and makes me think in new directions by connecting things that weren’t before. It also gets rid of that dreadful moment of the blank page at which you stare, unsure of where to start writing. Now, I can just go into my permanent notes section, look around a little, and find an intriguing little thought to put at the beginning of whatever I’m writing and take it from there.

References

Ahrens, S. (2022). How to Take Smart Notes. One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking (2nd ed.). Sönke Ahrens.

Klinkenborg, V. (2012). Several Short Sentences About Writing. Ecotone, 7(2), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1353/ect.2012.0012